The News You See, The News You Believe

The Shifting Landscape of College Students, News, and Information Engagement

by Andrew Pommer

The TikTok presidential election — words that strike fear into every moderately informed citizen. As political campaigns shift from traditional speeches and debates to viral videos and trending hashtags, the way we engage with candidates — and fact itself — is rewritten in real time.

No longer only filtered through careful journalism or debate stages, narratives are now crafted in seconds, designed to catch a viewer’s eye in the endless scroll. As social media takes on an increasingly prevalent role in information dissemination, the question looms: What does it mean for our democracy when public opinion is formed through memes, sound bites, and 10-second clips?

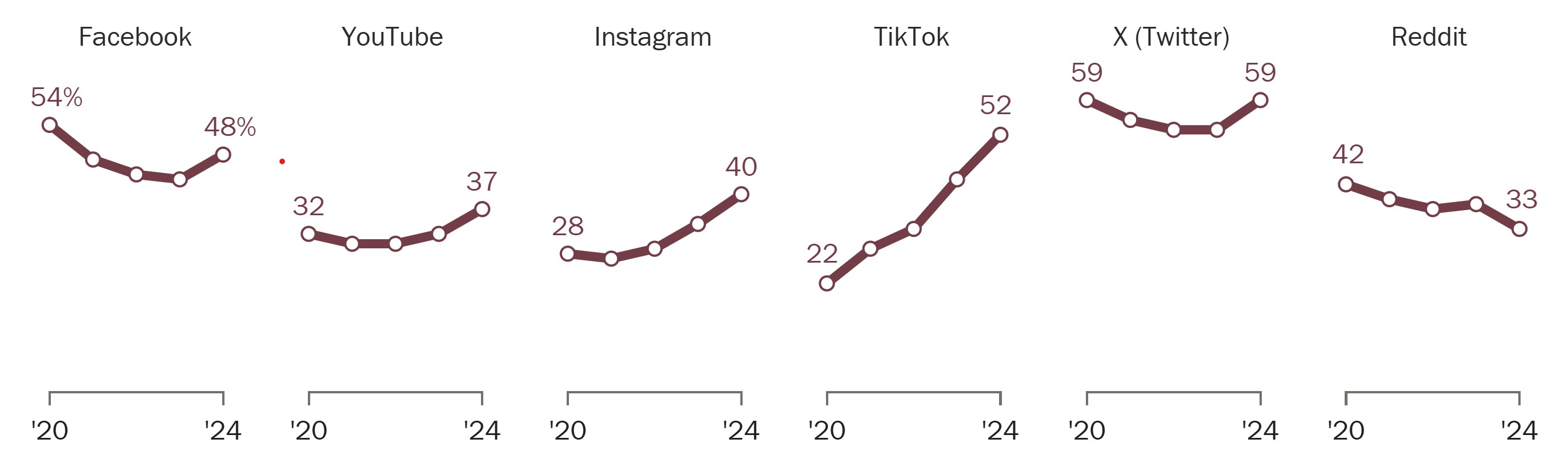

According to the Pew Research Center, most users of social media sites are increasingly relying on them as a regular source of information, as shown below.

Recognizing this shift, journalism professor Dr. Kylah Hedding, who teaches PR and Strategic Communications courses here at the University of Iowa, has been surveying how university students get their information.

Hedding, who was previously employed with the American Water Works Association (AWWA), worked alongside engineers and scientists, translated technical information in a manner consumable for non-experts. This experience, she notes, was invaluable in teaching her the importance of clear, accurate communication — skills she now passes on to her students at Iowa.

“One question I actually do ask my students in these beginning-of-the-semester surveys is if they had any media literacy training in junior high or high school, and almost none of them have,” Hedding said.

And in an age where anyone with a smartphone can be both a consumer and a producer of news, teaching students how to identify credible sources has become more critical than ever. And unfortunately, poorly informed content isn’t always as easy to see through, such as the “TidePods Challenge.”

“Students are bombarded with so much information that it's hard for them to figure out who those trusted sources of information should even be,” Hedding said.

According to Hedding, the lines between journalism, commentary, and plain opinion are increasingly blurred, sometimes making it challenging to discern fact from fiction.

“Be a consumer of media, and good media, not exclusively what ‘JoeShmoe427’ says on Twitter,” Hedding said.

So where do students get their information? Who are their trusted news sources? Beyond talking with Hedding, where she shared the results of her surveys, I conducted a couple of polls taking a random sample of UI honors and non-honors students.

Throughout my questioning of honors students, I discovered their top three most influential informational sources are online newspapers, their friends, and TikTok, respectively. Contrasted to non-honors students, whose habits differ, they gather most of their information from TikTok, parental or guardian figures, and Instagram, YouTube, and Podcasts.

Results of honors and non-honors students results are peculiar relative to the results of Hedding’s surveys of journalism students, who she says are “a little bit more invested in consuming some news than others.”

According to self-reporting done by her pupils over multiple courses, they recorded receiving their information through mainstream media news alerts, Apple News, and — you guessed it — social media.

These results can come across as confounding due to the similarities and differences in how students ascertain their news. While students specializing in journalism may prioritize established publishers, a common theme across all interviewees is the prevalence of pedagogy via social media.

“When using [social media], I remain skeptical of anything that feels overly partial,” said UI Honors student Mason Dormire. “Though when I check the news, I know there's editors and fact checks, making it more credible than Facebook,” they continued.

When asking a non-honors student, Lucas Cherry, about his primary information source, Instagram, he said: “It’s easy, and there’s no shortage of intriguing opinions shared. However, I recognize that the algorithm tailors my feed to posts I interact with.”

Despite nuanced differences in primary news sources, secondary and tertiary information gathering outlets were almost always social media apps. According to a Gallop News survey, the average US teenager spends over 4.8 hours per day on social media — a staggering fifth of the day.

The reach of social media presents both strengths and weaknesses for news dissemination. On the positive side, it offers broad access to multiple viewpoints, allowing students to read from a wide range of perspectives to extend their understanding of complex issues. Friends and family may even share articles that students might not otherwise come across, creating an informal “news-sharing” network within social circles.

“Friends and family actually can be an interesting way to get news because, a lot of times, a friend or a family member of mine will send a news article to me that I haven't seen because they have a different news diet than I do,” Hedding said.

But social media comes with a catch. The same algorithm that delivers curated content can also create echo chambers, reinforcing users’ existing beliefs as they engage with similar content. When users repeatedly encounter confirmation of their pre-existing beliefs, their views become more rigid, resulting in the deviation from pursuit of truth.

Echo chambers can reinforce an existing opinion within a group and, as a result, move the entire group toward more extreme positions.

“It’s super easy to get news on [social media], and it can be super addictive,” Hedding said. “But you have to be aware that the algorithm is feeding you a lot of information, often unequal when it comes to veracity.”

In this evolving media landscape, the rise of independent media platforms, such as podcasts and YouTube channels, has also transformed how news is consumed. These platforms offer an alternative to traditional news sources, often presenting content that is more relatable or tailored to niche audiences.

According to the Pew Research Center, over eight out of 10 adults in the United States have used YouTube — and nearly all Americans below 18.

Unlike traditional media, independent creators are less regulated and may lack the training to responsibly cover complex or sensitive topics. Users often find themselves prioritizing clicks over credibility, with titles like “You Won't BELIEVE What THIS Politician Said on TikTok!” or “This Conspiracy Theory Actually Makes Sense—And It's TERRIFYING!”

So what are we to do? Is there any way to effectively combat the ill-informed, algorithm-chosen, begging-to-be-clicked-on content? Thankfully, Hedding has countermeasures for us.

“I think one solution is to curate your social feeds as best as you can,” Hedding said. “Figure out who are some organizations and specific individuals that you can trust. And then pay attention.”

Hedding notes herself as a Twitter — now named X — user.

“I actually make a lot of use of the Twitter Lists,” she says, describing her various Lists, or self-selected groups of accounts and categories, of reliable sources for a wide array of topics, like politics, environmental issues, and sports. “But again, just making sure you're supplementing that with news from media organizations that have some editorial processes for helping determine what is and isn't true or what is or isn't important for us to know.”

Hedding’s approach underscores the importance of being proactive in navigating the digital information landscape.

“You can’t just rely on the algorithm to serve you your news,” Hedding said. “It’s crucial to take an active role in curating your feed and seeking out diverse, credible sources.”

This proactive stance is essential, especially in a time when misinformation can spread faster than the truth. Hedding emphasizes students should critically analyze incoming information, not just mindlessly consume it.

“It’s about asking the right questions,” she said. “Who wrote this? What are their credentials? What sources are they citing?”

By cultivating a habit of skepticism and inquiry, students can develop a more nuanced understanding of the issues at hand. This practice encourages them to sift through the noise of social media and identify reliable reporting, ultimately fostering a more informed electorate.

As the “TikTok presidential election,” as Hedding coined it, loomed on the horizon, rose, and peaked in early November, the call for media literacy moving forward becomes an imperative rather than a choice.

Students today are at the forefront of a rapidly changing landscape where the way information is consumed can shape the very fabric of democracy. By engaging with credible sources, critically assessing the information presented, and actively participating in the digital discourse, they can transform themselves from passive consumers into informed citizens.

Let us remember that being an informed citizen is not just a passive state; it requires active participation, discernment, and a commitment to truth. It is essential for individuals to take ownership of their media consumption, striving for a more informed and engaged electorate.

Only then can we preserve the integrity of public discourse and uphold the democratic values that underpin our society.

—

Citations

Liedke, Jacob, and Luxuan Wang. “Social Media and News Fact Sheet.” Pew Research Center, 17 Sept. 2024, www.pewresearch.org/journalism/fact-sheet/social-media-and-news-fact-sheet/.

Rothwell, J. (2023, October 13). Teens Spend Average of 4.8 Hours on Social Media Per Day. Gallup. https://news.gallup.com/poll/512576/teens-spend-average-hours-social-media-per-day.aspx

About the Author

Andrew Prommer is a third-year honors student double-majoring in finance and business analytics and information systems with a minor in computer science. He anticipates pursuing a career as a data analyst.