Cultivating the Conversation

How A UI Student Organization Fosters Dialogue About Eating Disorder Awareness

by Virginia Simone

I remember the moment, four years ago, when it sank in that I was dying.

I was sitting at the kitchen table with my parents on both sides of me and my computer propped up in front of us. On the screen was the woman who would save my life.

“I’m worried about your heart,” she told me through the call, her voice gentle. “If we don’t get you in treatment soon, it’s going to fail.”

I didn’t understand what she was saying. I stared at the screen, trying to make sense of her words.

I’m 16 years old, and my heart is failing.

Slowly, I stood up from the table, and I walked away. I couldn’t walk away from reality, though, and it was only a few weeks before I was sitting in another Zoom meeting, this one the orientation for my in-patient eating disorder hospitalization.

I would spend the next three months talking about feelings of anxiety and unworthiness and, of course, gaining back the weight I’d lost trying to control those feelings.

This is my story, but it isn’t a unique one. Tens of millions of Americans have or will have experience with disordered eating and body image struggles in their lifetime, but stigmas keep many from asking for help.

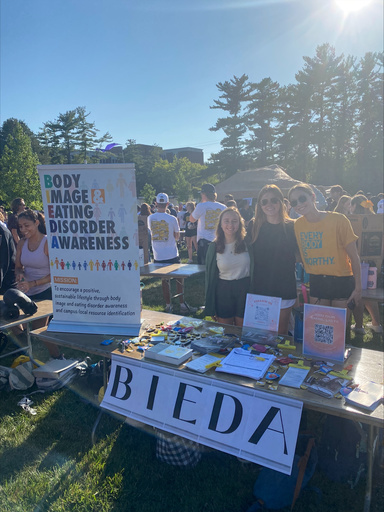

Photo by Holly Nicely.

BIEDA, or Body Image and Eating Disorder Awareness, is a student organization at the University of Iowa that is committed to changing the narrative. The organization is an affiliate of the Eating Disorder Coalition of Iowa, or EDCI, and its official mission statement is “to encourage a positive, sustainable lifestyle through body image and eating disorder awareness and resource identification.”

In other words, BIEDA gets people talking.

“Offering a safe space for conversations about body image, self-esteem, and mental health can be very beneficial to those who are struggling,” co-president and honors student Taylor Daniels said.

Daniels hopes their work will shed light on “the importance of not letting these issues people may be facing go unnoticed.”

“It’s very taboo, and people don’t like to talk about it,” fellow co-president Natalie Schloss said.

Now a senior, Schloss has been breaking the silence since joining four years ago. “I wanted to show other people it’s not something that has to be hidden or quiet.”

Dr. Holly Nicely is a BIEDA advisor and the eating disorder services coordinator at the UI’s University Counseling Services (UCS). Nicely said while eating disorders themselves have been around for a long time, this kind of discourse is a newer and incredibly needed development.

“Something I love about this generation is that folks are really questioning the ideals that they were raised with in diet culture,” Nicely said. “In generations past, they may have struggled in silence. They wouldn't have gotten help or identified even what they were thinking or doing as an eating disorder, and now folks are recognizing that as an issue.”

Still, certain populations are at greater risk of going untreated or unrecognized because of barriers like stigma and misinformation, the most common being the idea that eating disorders have a distinguishable look.

The pervading image of a white, thin teenage girl as the beauty standard — which leads to eating disorders — is not only inaccurate but also very harmful.

Anyone who doesn’t fit within those parameters — people of color or with different body types, traditionally “fit” athletes, and males, to name a few — have a harder time identifying when they need help, and even more so, actually getting that help.

Colorado football alum and former Seattle Seahawk Patrick Devenny experienced this firsthand as he tried to maintain an image and physique for his sport.

In an interview for the Eating Recovery Center’s podcast, Mental Note, Devenny said he spent a long time just trying to convince himself and others what he was feeling was real.

“It was one of those things that caught me so off-guard but really made me realize the uphill battle associated with eating disorders in males,” Devenny said.

Now, Devenny has become an advocate for other males struggling, especially athletes whose careers are so closely tied to their bodies. This is why BIEDA asked Devenny to speak during its awareness week at the UI this past October. It partnered with UCS, Student Wellness, and the athletics department to bring Devenny’s story to as many people as possible.

“The staff are the ones that help shape the college students’ experiences,” Schloss said of the interdepartmental collaboration. “[I hope] to see those partnerships grow so we can reach more people than just the students that we see.”

Another event that BIEDA did during its awareness week was a plant giveaway on the T. Anne Cleary Walkway. When students approached the table, BIEDA representatives would use the metaphor of caring for their new leafy friend to explain the importance of taking care of themselves.

Photo by Holly Nicely.

“Oftentimes, we're much kinder to animals or plants than we are to ourselves or our own bodies,” Nicely said. “We talk about how you wouldn’t have a pet or plant that you didn’t adequately nourish … [We encourage] really trying to treat yourself like you would treat someone you care about.”

After the giveaway, which happens once each semester, the campus is speckled with little green reminders of self-love.

“I think getting people to be kind to their own bodies and nurturing to themselves helps them in every aspect of their life, including academics.” Dr. Alicia Vance Aguiar, a BIEDA advisor and registered dietitian, said.

This is something that is especially timely for this generation of college students, who have experienced an unprecedented amount of change during their academic careers. Disordered eating and body image issues thrive in times of uncertainty, and 2020 provided plenty of it.

When the world shut down that March in light of the COVID-19 pandemic, I struggled to cope. What mattered most to me — my family, my community, my education — felt vulnerable to collapse at one wrong move.

I was paralyzed by the fear that I would make that one wrong move. I was afraid I would bring home a virus that would take the life of my dad, who has a lung disease that made him extremely high-risk, or that I’d cost my family money we couldn’t afford to spend after my mom’s cut in hours if I filled my plate at dinner.

The only way I knew how to ease the burden my family was carrying was by making myself smaller. By taking up less space. By needing less.

I was not alone in these fears or in my desperate attempts to ease them. Millions of Americans were falling into the same trap alongside me. However, resources like treatment, therapy, education, and organizations like BIEDA show there is hope. They deconstruct the societal norms that perpetuate the issue and teach healthy coping skills to replace the dangerous ones we create for ourselves.

And in doing so, they save lives.

Four years after my own treatment, I am still very aware how lucky I was to have access to that kind of support and education. Today, because of people like the student advocates in BIEDA who show others they aren’t alone, I can say I am 20 years old and my heart is no longer failing.

About the Author

Virginia Simone is a second-year creative writing student. She is from San Antonio, Texas, and now lives in Denver, Colorado. Currently an editor’s assistant at University of Iowa Press, she plans to pursue a career in editing after graduation.